By Jason Apollo Voss

Today we continue our two-part dive into share repurchase programs, trying to answer an important question for financial analysts. Considering the trillions of dollars that firms have spent over the years buying back shares — how can one determine whether that’s the best use of a company’s capital?

The information to answer that question is tucked away in a company’s Consolidated Statement of Shareholders’ Equity. In my previous column we reviewed how the Statement of Shareholders’ Equity is constructed using microchip technology company Nvidia (NVDA) as an example.

Now let’s study the data that Nvidia has disclosed on that statement in recent years, to analyze Nvidia’s own share repurchase spending.

First, we should note that Nvidia’s disclosure on its stock-based compensation program is excellent; the company even attributes issuances to different parts of its organization. That, in turn, allows us to do an interesting analysis to answer the question: Is Nvidia getting a good bang for the buck from its research and development department stock options program?

Starting the Analysis

To begin, think of Nvidia’s options grants as an investment. Like any investment, it should generate a return on capital — and like all returns on capital, calculations are done over an investment time horizon.

In its Note 4, Nvidia says that its vesting period for options is 2.5 years. So if its options program is structured well, then we should see an increase in revenues about 2.5 years after an investment in R&D. Given that Nvidia is competing in an industry where the technology turnover is rapid, it’s reasonable to think that two to three years out, its R&D ought to drive a large proportion of new revenues.

So how did Nvidia actually perform?

In 2019 Nvidia expensed $336 million in its stock options grant (according to Note 4) to its R&D team. Total R&D expense for that year was $2,376 million, meaning stock option incentives were approximately 16.5 percent of R&D expense.

How much did revenues grow by two years later? By $4,959 million ($16,675 million in 2021 – $11,716 million from 2019).

This increase may not entirely be attributed to new products; some of it doubtless came from sales to new customers and new regions. Nonetheless, Nvidia managed to have an incremental revenue increase relative to its R&D expense from two years prior of 208.7 percent. (That is, $4,959 million in incremental revenues after t + 2 years ÷ $2,376 million in R&D expense in time t.) Not bad.

Because of Nvidia’s excellent disclosures, we can improve on this blunt force calculation even more (and we will, below). Nonetheless, this evaluation of R&D can be done for other companies, too.

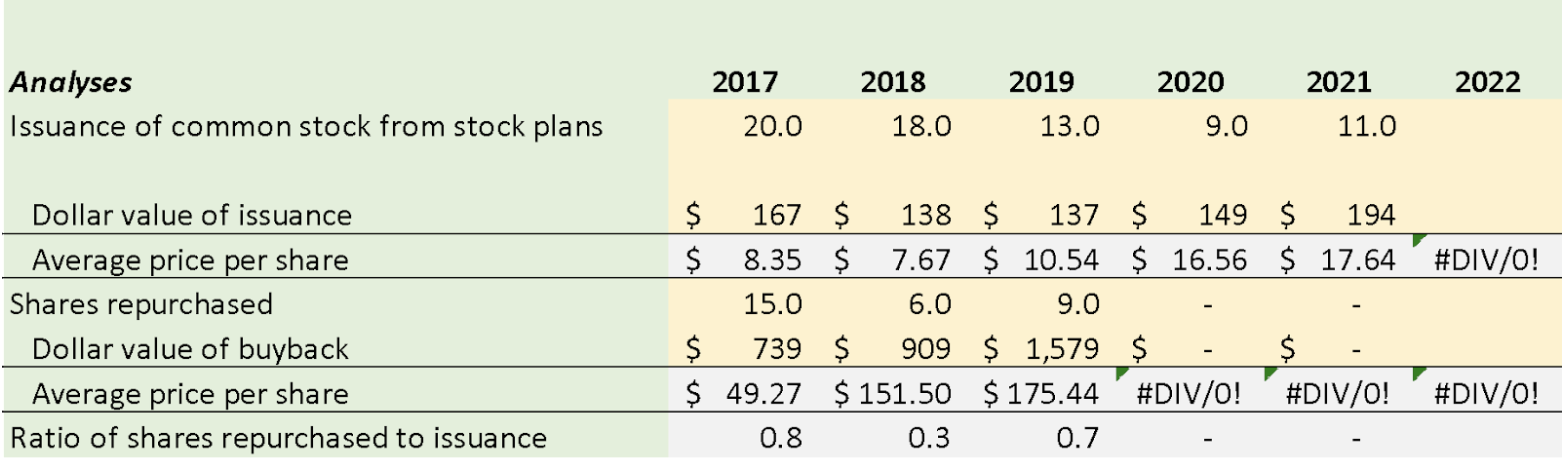

Next up: let’s answer some of the basic questions about share repurchase programs. The following summary table created by Calcbench is helpful in answering our questions. (Calcbench subscribers proficient in Excel and XBRL can do this themselves; or Calcbench can provide help upon request. Also, those DIV/0 errors in 2020 and 2021 happen because Nvidia stopped buying back shares in those years.)

Are these programs just offsetting share issuance to execs and employees?

If the answer to this question is “yes,” then it might be that the company is managing its earnings per share via its share repurchase program. In Nvidia’s case, however, based on this analysis, the answer at first glance is likely no, because its ratio of shares repurchased to issuance is less than 1.0. This means that the company’s share buyback program is not fully offsetting share issuance.

When coupled with the analysis above about the incremental revenue achieved by the company relative to its R&D spend (including options issuance), then we can conclude that Nvidia’s repurchases are not just offsetting share issuance to execs and employees, since the repurchases are also earning a return on their R&D. In other words, Nvidia’s incentives seem to be driving better business outcomes.

Are these programs simply a way of managing earnings per share?

In Nvidia’s case, the answer seems to be that it isn’t massaging earnings per share via its share repurchase program. If a company were trying to massage EPS through share repurchases, then its ratio of shares repurchased to issuance would be above 1.0 — meaning, it would be buying back more shares than it was issuing. As we just noted above, Nvidia isn’t doing that.

Are these programs a better use of capital than other types of investments, such as in R&D?

That’s a difficult question to answer in Nvidia’s case, because we can’t ascertain from its disclosures something equivalent to a “same store revenue growth” estimate.

That is, what portion of sales growth each year is attributable to new products and new markets versus old customers buying more of what they have to offer? Knowing the answer to this would allow us to identify new revenues that are a result of R&D, versus a return from employees working harder or old customers buying more. A review of Nvidia’s Management’s Discussion and Analysis and its discussion about revenues doesn’t help either, because Nvidia doesn’t provide a “same store revenue growth” type figure.

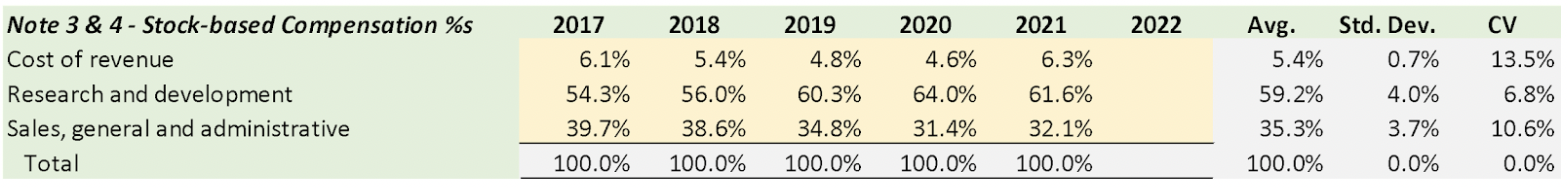

One possible way to estimate the effect of this is to look at Note 4 again and notice the proportion of issuance attributable to different parts of the company. (Again, this is only possible because of Nvidia’s excellent disclosures.)

That information for Nvidia looks like this:

We can treat as a hypothesis that Nvidia knows what it is doing when it incentivizes different employees within the company. Said differently, the above averages are likely good proxies for what proportion of new revenues can be attributed to its sales force (likely represented by the “cost of revenue” stock-based compensation), R&D scientists and their new inventions, and other employees (likely represented by the SG&A line, above).

Knowing this, we can make an estimate that 59.2 percent of new revenues stem from R&D. That comes directly from the table above, in the “Average” line.

That, in turn, allows us to re-evaluate the possible returns on R&D that Nvidia experiences. Incremental revenues of $4,959 million (from earlier) x 59.2 percent (assumed contribution attributable to R&D efforts from our table above) = $2,936 million of incremental revenues due to R&D. R&D expense from 2 years prior was $2,376 million. Meaning the total return in two years is 23.6 percent.

By contrast, let’s look at the amount of value-add of the share repurchase program. In 2019, Nvidia bought back 9 million shares of stock according to its Consolidated Statements of Shareholder’s Equity, for a price of $1,579 million. The average price per share of these shares was therefore: $1,579 million ÷ 9 million shares = $175.44. As of two years later at the end of fiscal 2021 Nvidia stock was trading at $129.90 (closing price on 29 January 2021), or a two year total return of: -26 percent.

Ouch! Their share repurchases seem to have lost them money. But wait, there’s more!

Recall that Nvidia said its options vest over 2.5 years? So we should look at the three-year period, too. The closing price three years later was $251.04, or a three year total return of: 43.09 percent.

I know what you are thinking, however: What about its stock price at the 2.5-year mark, to match the options vesting period with outcomes? Nvidia’s closing stock price at the end of July 2021 was $197, for a total return of 12.3 percent.

What this highlights is that research is hard; lots of our work is as much art as it is science. Two of the three periods examined above (the 2-year and the 2.5-year periods) actually look as if Nvidia’s share buybacks are not as beneficial as a straight investment in R&D.

But our analysis is not complete because there was also a boost to earnings per share due to Nvidia’s buybacks. The value-add is measured as:

- Earnings per share as reported 2019: $4,141 million in net income ÷ 608 million shares outstanding = $6.81

- Earnings per share, without 9 million shares bought back = $4,141 million ÷ 617 million shares = $6.71

- So, an additional $0.10 per share in Nvidia EPS cost $1,579 million, versus total net income of $4,141 million and EPS without the buyback of $6.71.

So far our analyses seem to suggest that share buybacks are not earning as high a return for Nvidia as its R&D program is earning. For completeness, though, perhaps the company is buying back shares because of the price per share effect? To do this analysis we:

- Multiply that $0.10 increase in EPS by its P/E ratio of 19.1 (which is $129.90 price per share ÷ $6.81 EPS). This gives us a possible increase in market cap of $1,907 million.

Again, the company spent $1,579 million to get a possible valuation boost of $1,907 million. What if we look at the 2.5-year period? To calculate the P/E ratio at the 2.5-year mark we need the EPS figure from Nvidia’s third-quarter 2020 through to the end of second-quarter 2021.

This is a bit tricky to calculate, but using the figures from annual and quarterly filings for the periods in question, we can figure out that Nvidia’s EPS for that period was $8.11. Its stock price at Aug. 1, 2021 was $197, which gives us a P/E ratio of 24.3. Our estimate for the boost to market cap is therefore $2,429 million versus a capital outlay of just $1,579, or a return on investment of 53.8 percent. By this calculation, it looks as if the buyback is inexpensive and actually a creation of capital for shareholders.

What is fascinating, of course, are the possible feedback effects of the buybacks. That is, the company buys back its shares and earns a valuation bump. That, in turn, leads to enthusiasm for the company’s share price performance, which results in an even higher multiple. Something to ponder as you await that next earnings release.

Epilogue

Our two columns on share buybacks provide the basis for any financial analyst to look more critically at a firm’s share repurchase programs. We do have two final points worth noting.

First, Calcbench has designed a template to let you import as-filed Statement of Shareholders Equity from any firm; we encourage you to download it. Data diehards can also use our API if you’d prefer. Drop us a line at info@calcbench.com and we’ll get you squared away.

Second, after we wrote these two columns examining Nvidia’s 2017 to 2021 annual reports, the company filed its 2022 report. Those numbers look a bit different for several reasons, including a would-be merger that ultimately was called off and a 4-to-1 stock split. Don’t let that throw you; the analytical techniques discussed here, plus the Excel templates Calcbench has cooked up, are a solid foundation for you to conduct your own analysis of the firms you follow.

This is an occasional column written by Jason Apollo Voss — investment manager, financial analyst, and these days CEO of Deception and Truth Analysis, a financial analytics firm. You can find his previous columns on the Calcbench blog archives, usually running every other month.