By Jason Apollo Voss

Back when you were learning accounting, perhaps your professor, textbook author, or somebody else explained that rather than relying on the cash flow statement reported by a company, you can create your own cash flow statement from information on the firm’s income statement, balance sheet, and footnotes.

If you’ve never done this exercise, give it a try. You’ll be surprised by the insights that you can glean from doing it. Those insights gained include:

- How the company operates, at a much more granular level.

- How aggressive or conservative the management team is, as represented by its accounting.

- How transparent the management team is.

- What management’s character is.

- And more.

How to Create Your Own Cash Flow Statement

For those not in the know, let’s walk through how to create your own cash flow statement with disclosures in a company’s income statement, balance sheet, and footnote disclosures. (We’ll use the indirect method, since most companies don’t use the direct method and our comparisons wouldn’t be harmonious. Plus, most companies don’t report the values necessary to compile a direct-method cash flow statement.)

Here are the steps for creating your own cash flow statement. I’ve also added in parentheses where you can usually find the necessary information.

Generally, you can follow the same flow of accounts that the company uses in reporting its own cash flow statement, starting with its calculation of operating cash flow, continuing on to cash flows from investing activities, and concluding with cash flows from financing.

- To create an independent operating cash flow estimate, begin with net income as reported (income statement).

- Add back any non-cash expenses that were subtracted to derive net income as reported on the income statement (usually on the income statement, sometimes in the footnotes).

- Calculate the changes in both current assets and current liabilities for the period, compared to some prior period (balance sheet). Typically you’ll compare year over year, or quarter over quarter.

- Using those changes in current assets and current liabilities, add or subtract these changes to the numbers derived in steps 1 and 2 (balance sheet, and sometimes footnotes). Be careful! This can get tricky in which changes get added and which get subtracted, because it can seem counterintuitive. One useful tip is to imagine yourself as the business owner actually writing these checks and receiving these payments. It also helps to know the effect of the various accounts on a business. That is, what is their function? I find this makes tracking accounting flows much easier.

- As a general guide, if a current asset decreases it means that cash flow increases. If a current liability increases, it means that cash flow increases. For example, if accounts payable increase, it means the company is delaying payments on more of its bills and is preserving cash, so cash flows should increase.

- As a general guide, if a current asset increases that means that cash flow decreases. If a current liability decreases, it means that cash flow decreases. For example, though it may seem counterintuitive, if inventories increase that means the company spent more money building up its inventories, so cash flow should decrease.

Following steps 2 through 4 should allow you to arrive at operating cash flow.

For cash flows from investing activities, you follow the same protocols described above using the balance sheet’s non-current assets section, and look at the changes in values of those accounts. Be careful to look at non-depreciated values for property, plant and equipment, as well as non-amortized amounts for goodwill.

For cash flows from financing activities, follow the same protocols, but most of the changes are going to be in the non-current liabilities and shareholders’ equity accounts.

March through all of that, and you should arrive at an independent cash flow estimate.

An Example of Creating Your Own Cash Flow Statement

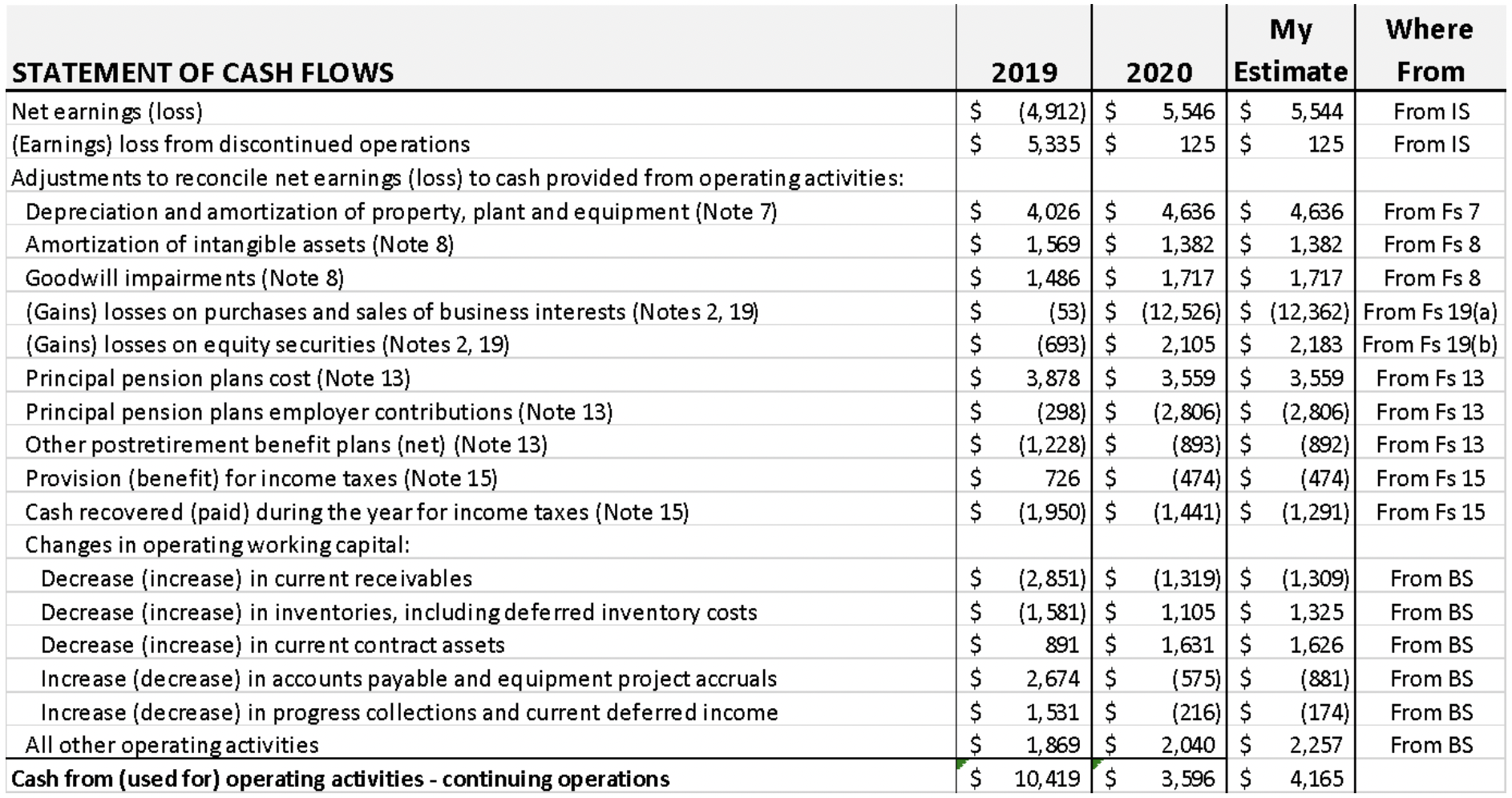

Let's use the disclosures in General Electric’s 10-K filing as an example. Here are the reported amounts from GE, along with my estimates for these same accounts. (The sources of the figures are shown in parentheses.)

As you can see from the above estimates, there is a difference of $569 million, or 15.8 percent, in GE’s reported cash flow from operations ($3,596 million) compared to my estimate ($4,165). (Also note that GE’s numbers are occasionally a tiny bit off, because the firm rounds the numbers it reports.)

While this may seem like a wide disparity, I must give GE credit. Why? Because my usual experience in doing this exercise is that it’s almost impossible to derive the values reported by companies in their cash flow statements. For example, years ago I did an analysis for Luis Vuitton. Items like depreciation were more than 100 percent off, despite a careful reading of the company’s 20-F and its many disclosures.

To my thinking, one of the great unaddressed issues in finance and investing is that deriving an accurate estimate of cash flow by this method is so difficult. If the accounting and disclosures are sound, we should be able to do this with ease.

But for GE, most of the numbers are exactly the same when comparing the amounts GE reports on its cash flow statement to those estimated by me, and gathered from the income statement, balance sheet, and footnotes.

In fact, of the above accounts shown, 15 of the 18 accounts are within 10 percent of one another. Trust me: this is not a bad result. That said, some of the accounts are wildly off — and this is where things get very interesting for a research analyst.

As an example, GE’s “(Gains) losses on equity securities (Notes 2, 19)” is 3.7 percent different. But if we examine the company’s footnote disclosure, there is nothing reported that accounts for the difference.

Next, take a look at the company’s “Cash recovered (paid) during the year for income taxes (Note 15)” which is off by a less respectable 10.5 percent. Yet, the amount I estimated comes directly from GE’s footnote.

What accounts for the difference? We don’t know. Nowhere in the financial statements are we given enough information to assess this for ourselves. In both cases, it appears that GE is underreporting its cash flows from operations.

You may think this is not so interesting. But within a company’s reporting, we would assume that the net working capital accounts — that is, the ones closest to being cash — should be the easiest for us to estimate, and the hardest to have discrepancies.

Wrong. In GE’s case these accounts are where everything starts to break down. For example, inventories are among the easiest of accounts for us to estimate: this year’s inventories minus last year’s inventories. But for GE, even when accounting for the inventory nuances reported in its Footnote 6, the estimated cash inflow should be $1,325 million. Instead it's a paltry $1,105 million.

This is mysterious, and suggests a class of questions derived from this exercise that we should direct at investor relations pros:

- What do we not understand about the company’s operations, such that our estimate is off? Or, assuming that we aren’t in error…

- Why is the company inconsistent in its reporting of accounts? Or, assuming that it is consistent…

- Why does the company not disclose enough information to allow us to estimate these accounts as a check on its disclosures? Or...

- Why is the company’s reporting so complex as to defy easy digestion of its information content? Or...

- What if something is underhanded going on?

Each of these are key questions that this exercise makes possible.

Continuing on with GE, the company’s accounts payable and equipment project accruals should also be easy to estimate from balance sheet entries — but they’re off by more than $300 million. Sadly, GE does not provide a reconciliation or explanation for what accounts for the differences. Ouch.

Most mysterious of all of GE’s operating cash flow accounts is its ill-defined, ill-described “All other operating activities.” Of all of the accounts where my estimate is off by more than 10 percent, this one concerns me the most. That single account, even accepting GE’s reported figure of $2,040 million, is a whopping 56.7 percent of its total reported operating cash flow of $3,596 million.

What’s going on in there? We have no way of knowing. The figure I estimated (of $2,257 million) took me nearly an hour to engineer by combining different accounts with one another. Still, my estimate is very different — and I have a masters’ degree in accounting!

In all likelihood, nothing nefarious is happening. Then again, investing is a lot like watching an automobile race: It's not worth watching to see people drive in circles for hours, but we pay close attention for the occasional fiery crash.

Conclusion

One way that investors can improve their results is to dive deeper into a company’s accounting. A time-tested method for doing this is to create an independently derived cash flow statement from a business’ disclosures in its income statement, balance sheet, and footnotes.

By comparing the reported figures with the estimated figures, many different insights may be gleaned about a prospective investment. Usually this is just a deeper understanding of the nuances of a company, but sometimes we can discover the ways that companies obscure their performance.

This is a monthly column written by Jason Apollo Voss — investment manager, financial analyst, and these days CEO of Deception and Truth Analysis, a financial analytics firm. You can find his previous columns on the Calcbench blog archives, usually running the first week of every month.