By Jason Apollo Voss

One way that a company can create the appearance of profitability through aggressive accounting is sleight of hand with how it capitalizes its expenses.

Capitalization of an expense, rightfully booked now, delays recognition until later; that improves net income right now. But wait, there’s more! Capitalization also puts an asset on the balance sheet that shouldn’t be there; making an aggressive firm look more financially sound, too.

So the capitalization of expenses is potentially both an offense against investors and a con. As with many accounting issues, however, judging a business’ capitalization practices can be tricky. It requires just that: judgment.

When should costs be capitalized? Two fundamental ideas.

The key question is when should costs be capitalized and when they shouldn’t. Fortunately, accounting standard-setters globally have provided some clarity with their well known “Matching Principle.” If you’re not familiar with this bedrock accounting concept, here is the definition from Wikipedia:

“[T]he matching principle instructs that an expense should be reported in the same period in which the corresponding revenue is earned, regardless of when the transfer of cash occurs. By recognizing costs in the period they are incurred, a business can see how much money was spent to generate revenue, reducing ‘noise’ from timing mismatch between when costs are incurred and when revenue is realized.”

Within this definition are two fundamental ideas:

- Benefits and the costs required to create them should be linked together for an accurate accounting of profitability for a given business activity.

- The time horizon used for examining the benefits and costs of a business activity should also be the same.

If you understand these two fundamental ideas, then you have a powerful evaluative mechanism for judging the way a business capitalizes costs — and whether this provides an accurate record of their profitability. Armed with these concepts, it’s also obvious that the problem of mis-capitalization of expenses is almost always a violation of the second fundamental idea: keeping the evaluative time horizon of both benefits and costs is the same.

In short, companies use capitalization to decouple expenses from their matching revenues by creating a separate, longer time horizon for recognizing expenses. Recognizing expenses over a longer time horizon makes each period’s costs look lower. Consequently, in the short-run, profits look higher, as do assets.

Example: Software as a Service (SaaS) Startup

Imagine you are a startup SaaS business struggling to demonstrate profitability to investors. Also imagine that your premium software has a high customer acquisition cost, but you’re confident that in the fullness of time you'll recoup that cost of bringing on board a new loyal customer.

Your belief is strong because you know that your software is unique and is vital for your customers to improve their businesses; and in turn you anticipate this will create customer loyalty. So while costs are high in the short run, you’re likely to have high profitability in the long run.

From an accounting perspective, you recognize revenues as soon as your customers sign their annual contract. Your research shows that your customers (a) have no substitute for your product; and (b) you likely have a three-year technological advantage over competitors. Therefore, you capitalize your customer acquisition costs over three years, confident that until a viable competitor for your product emerges, that you can count on good repeat business. You believe that you have provided the proper accounting for your situation.

Wrong! While it may seem that you are properly matching expenses to revenues by capitalizing your customer acquisition costs, you aren’t. Here’s why.

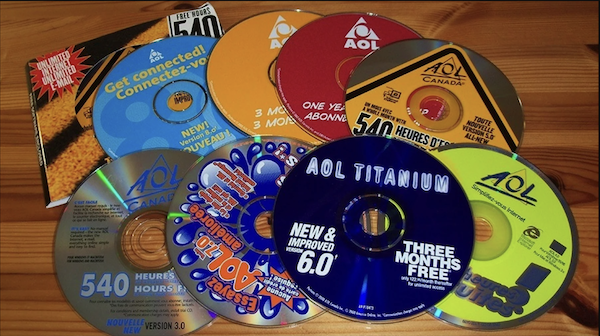

In a well-known case from the 1990s, America Online (AOL) was conducting its accounting in almost exactly the way I described above. In AOL’s case, the company was mailing nearly every household in the United States a CD-ROM with its software on it, for free. Interested customers would place the CD in their computers and then sign up for AOL. (If you are over 40, you remember exactly what we mean.)

AOL capitalized these customer acquisition costs because its research showed that customers were likely to be loyal and stick around long enough for collected revenues to be matched to the cost of acquiring the customers.

Well, the SEC had a different opinion. It likened these expenses to advertising costs — which are expensed in the same period in which they are incurred.

There is, however, an exception, and — you guessed correctly! — it requires judgment.

The exception is that if revenues are historically predictable, then the expense of customer acquisition may be capitalized over the length of a typical contract.

Unfortunately for AOL, the SEC argued that it was too new a company and that its future revenues were not predictable enough to qualify for the exception. Ruling in this way had a massive effect on AOL’s results and moved it from strongly profitable to a very large loss. Ouch!

For what it’s worth, I think the SEC had the correct assessment of AOL. As a research analyst at the time, anecdotally I knew from my experience (and those of friends and family), that what they really wanted from AOL was access to the Internet. In other words, as soon as a company could provide direct access to the web, and circumvent the AOL platform, customers would follow … and they did.

This underlines a point I’ve made in previous columns. As analysts, we must always understand the underlying real world economics of the businesses in which we invest. Then we must ask ourselves whether the accounting policies and choices of a company fairly represent the underlying economics. Here are some tips for evaluating proper cost capitalization by a business.

Typical Expenses and Their Capitalization Treatment

While it may seem that whether an expense should be capitalized is a bit tricky based on my AOL example, in most cases the analysis is straightforward. In fact, most of the large expenses incurred by businesses have well-documented, generally accepted accounting principles. For example:

- Inventories: expensed when the revenue for the good in inventory is sold.

- Advertising: expensed in the time period in which the advertising was run.

- Commissions: when a salesperson sells goods, any commission paid to the sales executive is expensed when the revenues are recognized.

- Prepaid expenses: a good case is insurance, which is always paid in advance and is expensed in the period in which the benefit was experienced.

- Research and development: because of the uncertain nature of R&D expenses they are typically charged now. The exception is expenses directly tied to a revenue-generating activity, such as software development.

- Depreciation: this is the classic example of accrual accounting, where the useful life of an asset is estimated and then depreciated over that time, rather than in the period in which it is purchased.

- Patents: the expenses incurred for filing for the patent and adjudicating patent disputes may be capitalized. The R&D expense incurred developing a technology cannot. Acquired patents and exclusive licenses may be capitalized at their purchase price (similar to goodwill).

Guidelines for Expense Capitalization Judgment

Any assessment should begin by reviewing the company’s approach to capitalization as revealed in the Accounting Policies section of its annual report. (Look for Item 8, just past the financial statements.) With these in mind, here are some guidelines for judging whether a company’s expense capitalization is legitimate.

- What is the time frame over which revenues for the product or product line are predictable? This time frame establishes the period for which expenses connected to generating the revenues should be matched.

- Regarding predictability of revenues: (a) Is this a product that has been sold for years, or a new product? (b) Is there a sales contract that obligates customers to purchase the product over a specific time frame?

- Do the expenses incurred now have staying power and benefit a future period or periods, akin to the purchase of property, plant and equipment? If not, they should be expensed now.

- Can expenses be directly tied to a specific (rather than general), revenue-generating activity? If not, they should be expensed immediately. An example is the payment of any general corporate expense, such as rent, where the entirety of the business benefits from the expense and is not tied directly to any revenue activity.

- Are any asset accounts growing significantly faster than the company’s operating expenses, as revealed by conducting a common-size over revenues analysis? If these assets are ones where management judgment is important (accounts receivable or inventories) then it may be time to dig deeper or ask management about these accounts. Why? Because accounts that are growing much faster than revenues, and where management has discretion, are vulnerable to being used to stash mis-capitalized expenses.

- Do the useful lives for assets that are capitalized match reality? For example, software and other technological assets clearly have short useful lives. Is the company reporting a useful life greater than three years? And so on for other assets: are their useful lives matching the underlying economics?

Conclusion

In conclusion, companies have incentives to report higher profits and assets now. One way they can improve both is to capitalize expenses that should not be. This capitalization con can lead to a distorted understanding of business performance and lead investors astray. By understanding the Matching Principle, you can decipher the correct analysis of a company’s expense capitalization, and avoid a burn by management.

This is a monthly column written by Jason Apollo Voss — investment manager, financial analyst, and these days CEO of Deception and Truth Analysis, a financial analytics firm. You can find his previous columns on the Calcbench blog archives, usually running the first week of every month.